Force and Motion

There must be Fifty Ways to Love Your Lever!

Overview

The purpose of these activities is to acquaint students with the principles of simple machines through a study of common utensils and tools. They begin by examining some of these devices, and trying to find their common features. Through this activity, they develop ideas about input, output, motion and force. Next, students identify the effort, fulcrum and load of each device, and then sort them according to class of lever. Then they trace and measure the input and output ranges of a pair of salad tongs, and relate these to the effort and load arms. Shifting the focus to force measurement, they use spring scales to determine the force needed to balance the return spring, as a function of length of the effort arm. Examination of the data leads to a discussion of the Law of the Lever, which is an example of the Law of Conservation of Energy, as well as the concept of Mechanical Advantage. Based on what they have learned, students redesign a doorknob to make it easier to turn.

Materials (quantities listed are on a per-group basis)

Scavenger Hunt/ Brainstorming

Procedure: Students are divided into groups. Each group is provided with a few mechanisms, including pop-up books, and asked to determine the characteristics they have in common. They then share these characteristics with the whole class, which uses the ideas from each group to formulate a master list of what constitutes a “mechanism.”

Then they look for additional examples of mechanisms, both from around the room, and also from among their personal effects. They check each device they think might be a mechanism to see if it meets the criteria they have established.

The job of a mechanism is to transform the force and motion supplied by the user at the input, to the force and motion needed to do a task elsewhere. This tells us some things these mechanisms have in common: each one needs a human being to operate it, and is designed to do a job. Some of the more obvious tasks are cutting, holding, and squeezing; but there are also mechanisms whose job is simply to fold or unfold, retract or extend, etc. When students look for common features of mechanisms, they may say, “All of them can grab something.” This statement might be true of a pair of pliers, an eyelash curler, a tweezers, a staple remover, and even a scissors or a nail clipper, but it would certainly not apply to an ice cream scoop, glue stick, pop-up book, folding chair or umbrella.

As they look around the room, students should be encouraged to extend their view of mechanisms to include such items as door knobs, light switches, door locks, doors, door knobs, cabinet handles, window latches, crank-operated pencil sharpeners, folding chairs, etc. There will also be mechanisms they have brought with them, These might include lip stick cases, retractable ball-point pens, book bag buckles, key chain latches, and so forth. Interesting issues may come up about whether books, cell phones, calculators, watches, etc. should be considered mechanisms. If the input and output are not distinct, as in a push button, it might be argued that the device is not really a mechanism.

Sorting

Procedure: Each group is provided with a variety of mechanisms. They are then introduced to the terms “fulcrum”, “effort,” and “load,” and asked to identify these points on several of their devices. They sort their mechanisms according to the arrangement of the effort, fulcrum and load: effort-fulcrum-load (1st class lever); effort-load-fulcrum (2nd class lever); or load-effort-fulcrum (3rd class lever).

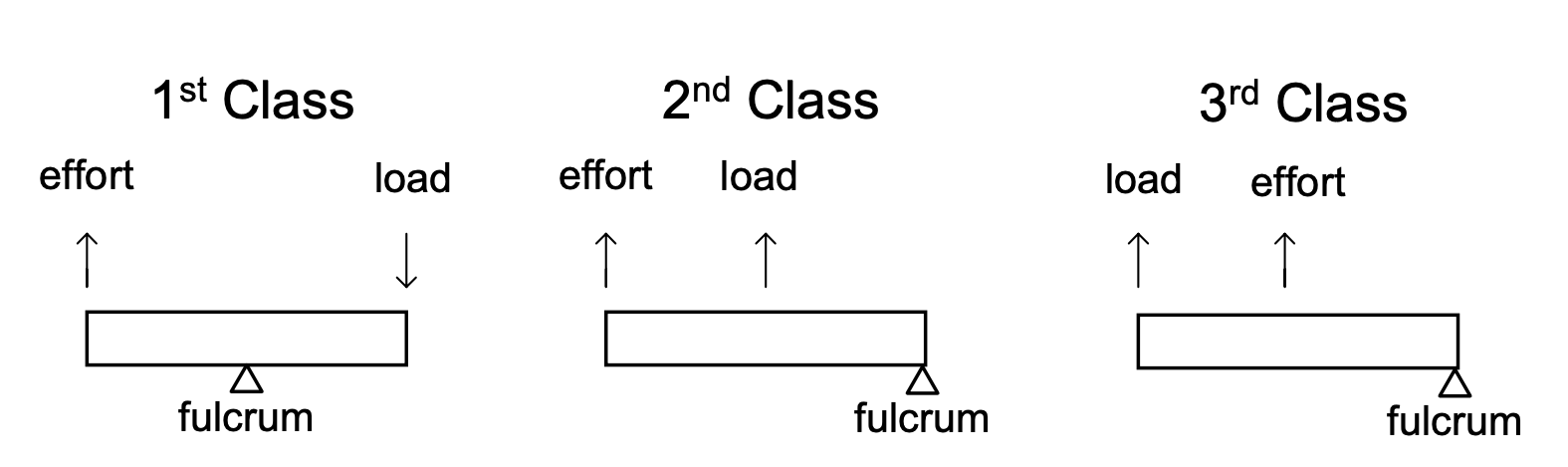

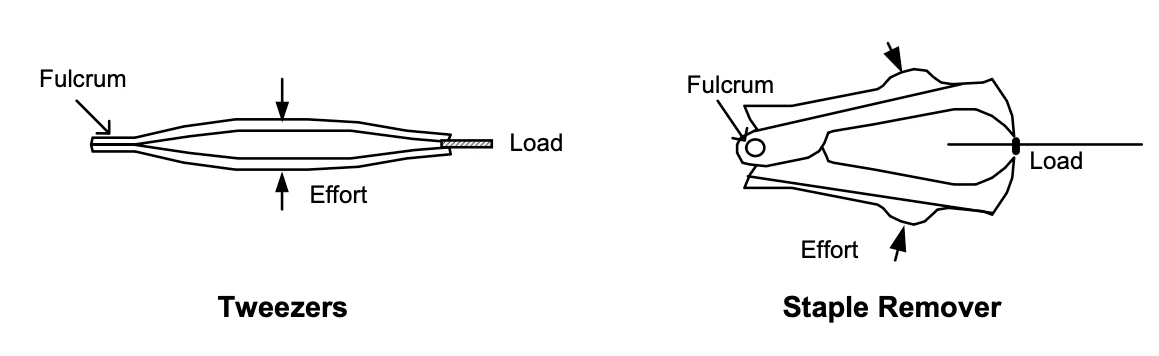

“Input” and “output” are general terms that could be used with any system. A special language is used in describing the most basic type of mechanism, the lever. The input is often called the effort, and the output is called the load. As with the terms “input” and “output,” both the “effort” and “load” could describe either a force or a location. In addition to the effort and the load points, every lever has a pivot that allows the rest of the device to rotate. We have already seen how rotation about the pivot causes the paths of motion to be arcs instead of straight lines. In the language of levers, the pivot is usually called the fulcrum. Several important characteristics of lever operation depend on the arrangement of the three elements: fulcrum, effort and load. There are three different permutations of these three. Based on these three arrangements, levers are categorized as first-, second- or third-class (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The three classes of levers

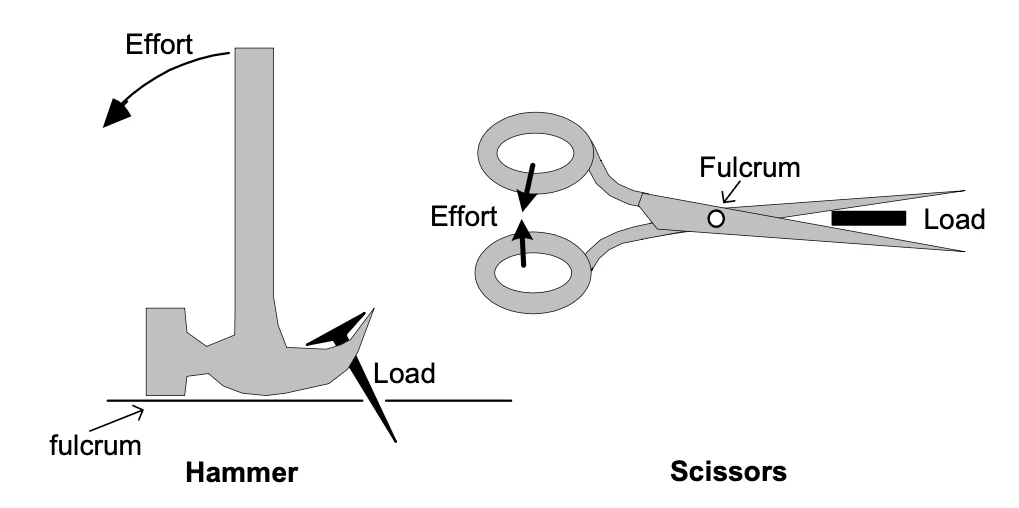

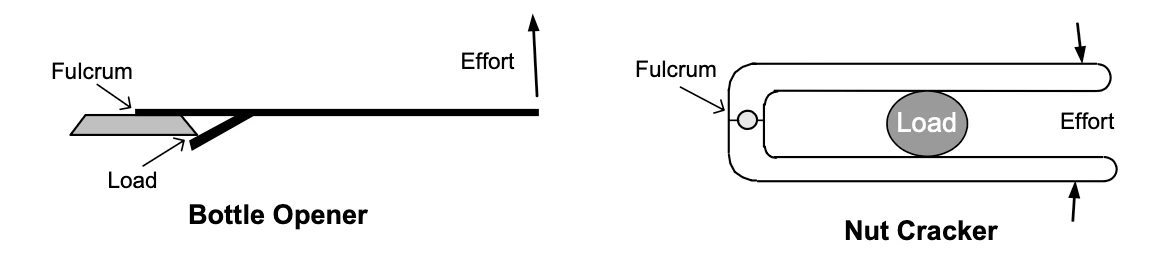

Figure 2: Examples of first-, second- and third-class class levers

To see what class a particular lever falls into, identify the fulcrum, effort and load, and compare their arrangement with the definitions in Figure 1. Figures 3, 4 and 5 show how this can be done for some examples of each class.

Figure 3: First-class levers

Figure 4: Second-class levers

Figure 5: Third-class levers

Analysis & Sketching

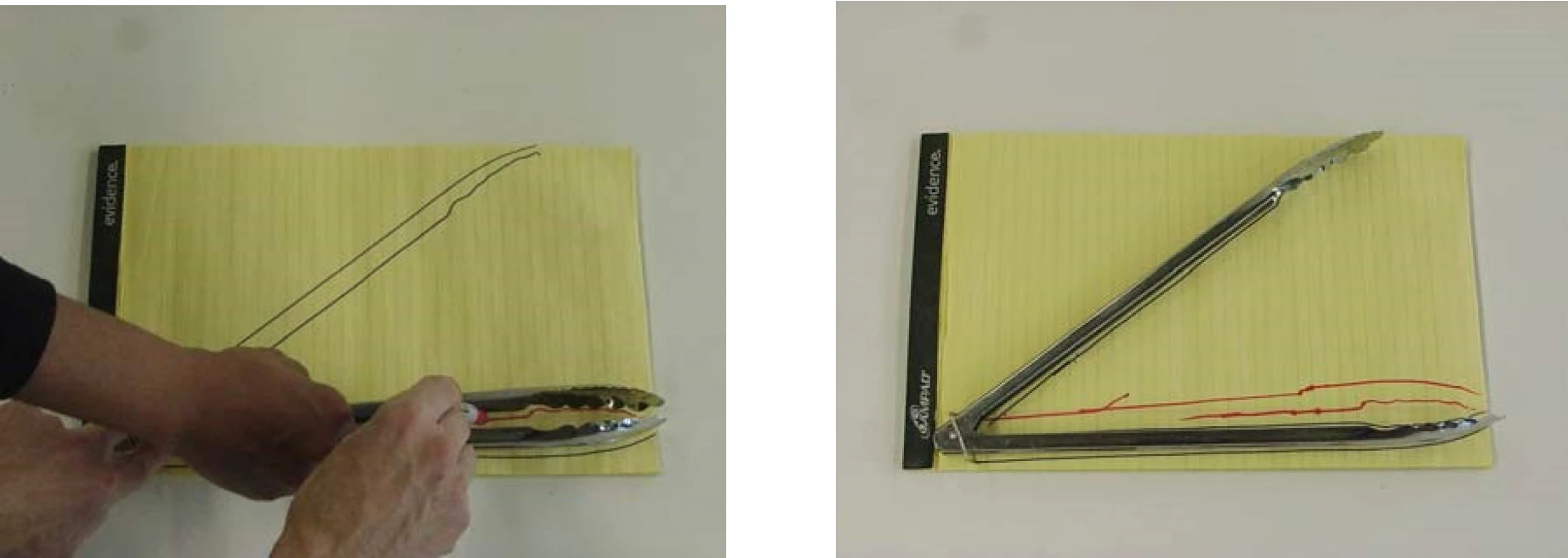

Procedure: Each group is provided with a pair of salad tongs for further study. He or she identifies the locations of the input and the output, and looks for the differences in the motion at each location. For example, the input and output might move in opposite directions; one might travel a shorter distance than the other; one might travel in a circle or arc, while the other might follow a straight line, etc. To make careful observations of these differences, it is useful to make a sketch. Here’s how:

Figure 6: Open and closed positions of a pair of salad tongs.

Figure 7: Input range (left) and output range (right) for the same pair of tongs

Measuring input and output ranges

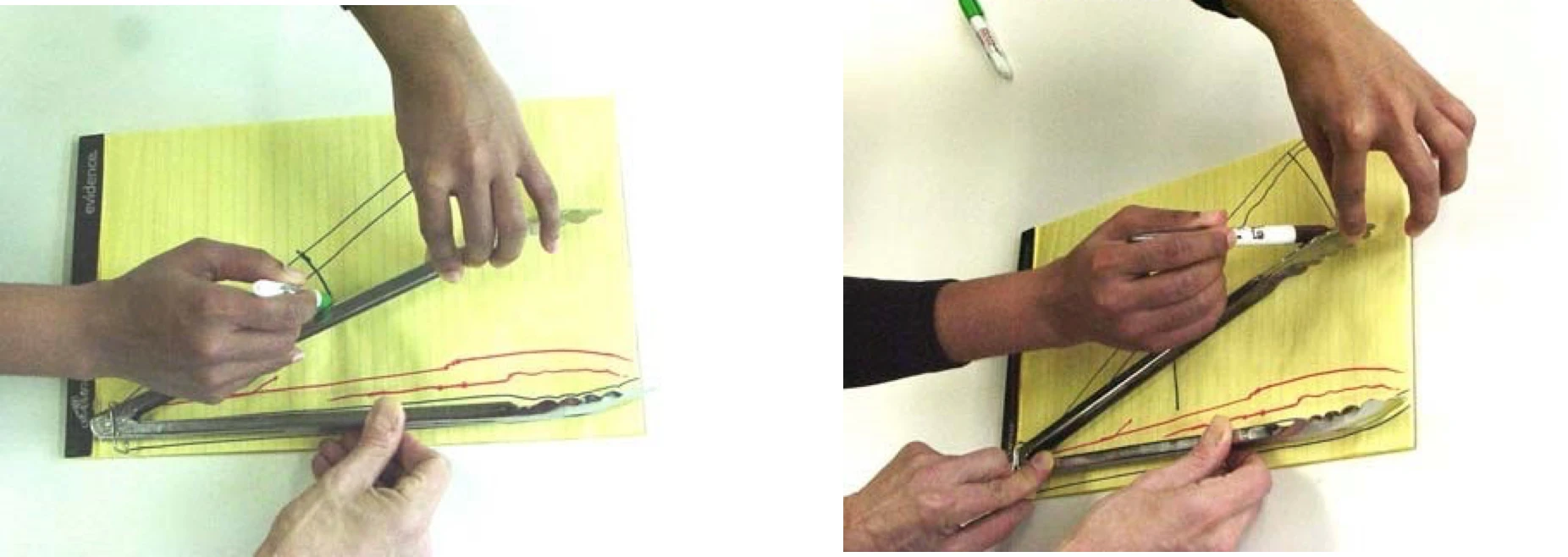

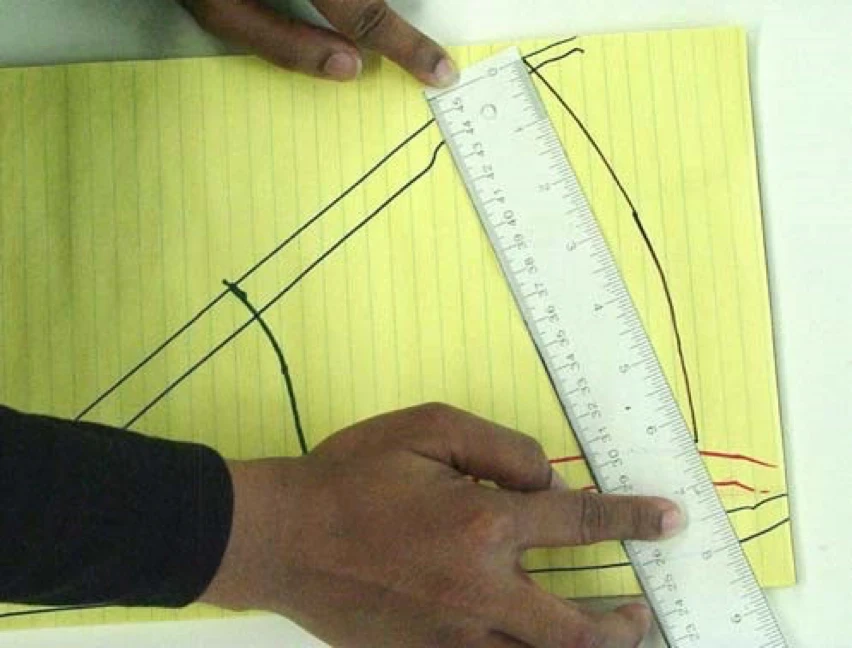

Procedure: Each group measures the two ranges of motion of a pair of salad tongs, which have been sketched in the previous task (see Figure 8). They then calculate the ratio of {(input range) : (output range)}. Students are then introduced to the terms effort arm (distance from fulcrum to effort point) and load arm (distance from fulcrum to load point), they measure these two quantities, and take the ratio {(effort arm) : (load arm)}. Then they calculate and compare the two ratios and see why they might be similar.

Figure 8: Measuring output range

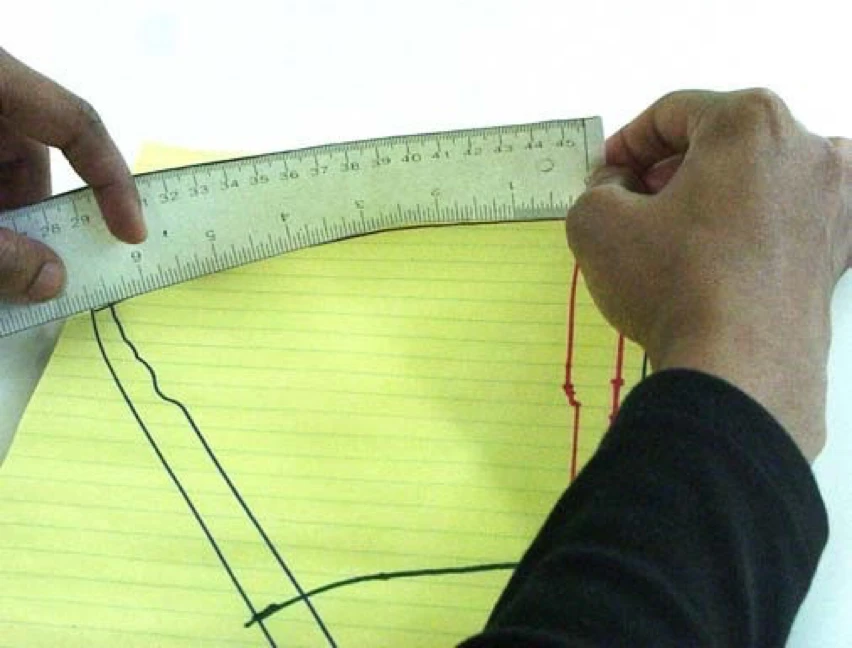

Students may find difficulty in measuring the length of an arc. Someone may suggest that it would be easier to measure from endpoint to endpoint – in other words, chord length instead of arc length (see Figure 9). Would chord lengths work just as well in the calculations?

Figure 9: Measuring chord length instead of arc length

Our only calculation will be to find the ratio:

$$

\frac{\text{INPUT RANGE}}{\text{OUTPUT RANGE}}

$$

So the question of arc length vs. chord length really comes down to this:

$$

\text{Does } \frac{\text{input arc length}}{\text{output arc length}} = \frac{\text{input chord length}}{\text{output chord length}}\text{ ?}

$$

This is an interesting exercise in plane geometry. To show that it does, you need to use similar triangles and the formula for arc length.

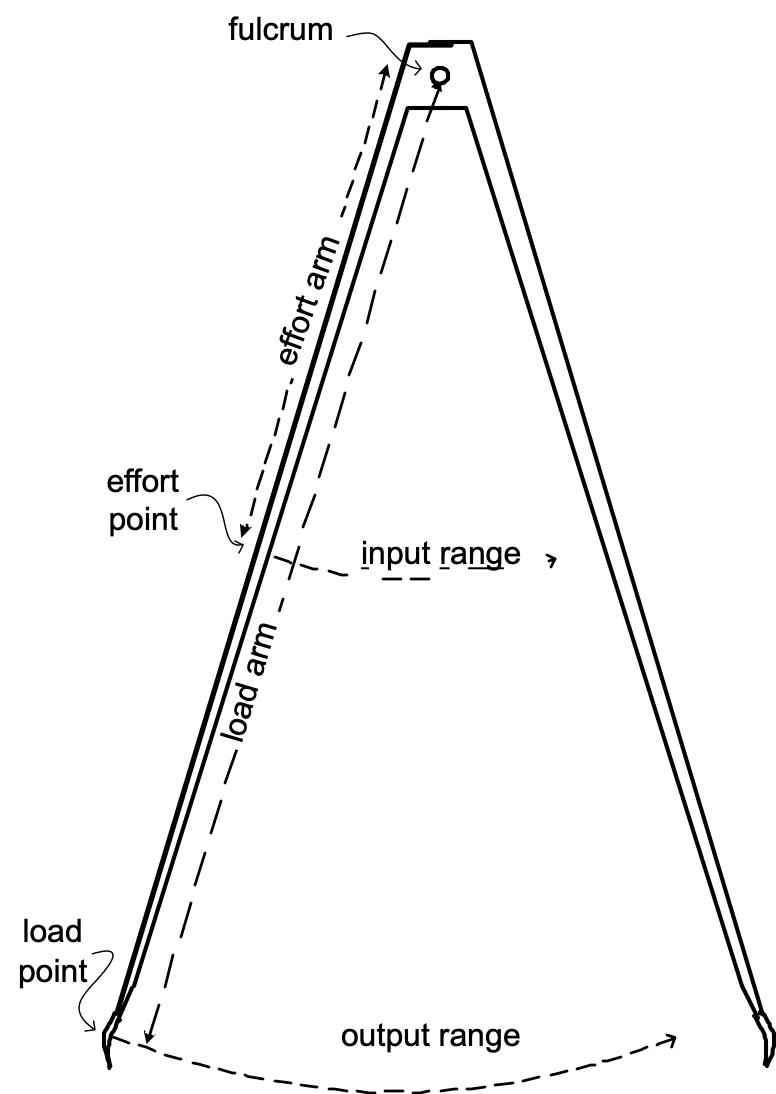

Regardless of which method is used, the ratio of {input range : output range} is the quantity that needs to be found. This ratio is so important, it has a special name: mechanical advantage. We’ll see why in the next task. Meanwhile, we need two more measurements to see where this ratio comes from. Students locate the fulcrum (pivot), and measure the distance from this point to the input, or effort point. This distance is called the effort arm. Afterwards, they measure the distance from fulcrum to load point, which is called load arm. Figure 10 shows all four measurements: input range, output range, effort arm and load arm.

The second ratio to calculate is:

$$

\frac{\text{EFFORT ARM}}{\text{LOAD ARM}}

$$

Now ask students to compare the two ratios. Both

$$

\frac{\text{EFFORT ARM}}{\text{LOAD ARM}} \text{ and } \frac{\text{INPUT RANGE}}{\text{OUTPUT RANGE}}

$$

should be about the same, and both are known as mechanical advantage. Showing that the ratios are the same is an exercise in plane geometry, which is already accomplished in the previous demonstration that

$$

\frac{\text{input arc length}}{\text{output arc length}} \text{ and } \frac{\text{input chord length}}{\text{output chord length}}

$$

Figure 10: Effort arm, Load arm, input range, output range

Collecting force and distance data

Procedure: Distribute a pair of salad tongs to each group. Each group uses a spring scale to measure the force needed to balance the return spring at various points along the arm of a salad tongs. They collect data showing the relationship between force and distance. These two variables are then multiplied to form a constant quantity called energy, illustrating the Law of Conservation of Energy.

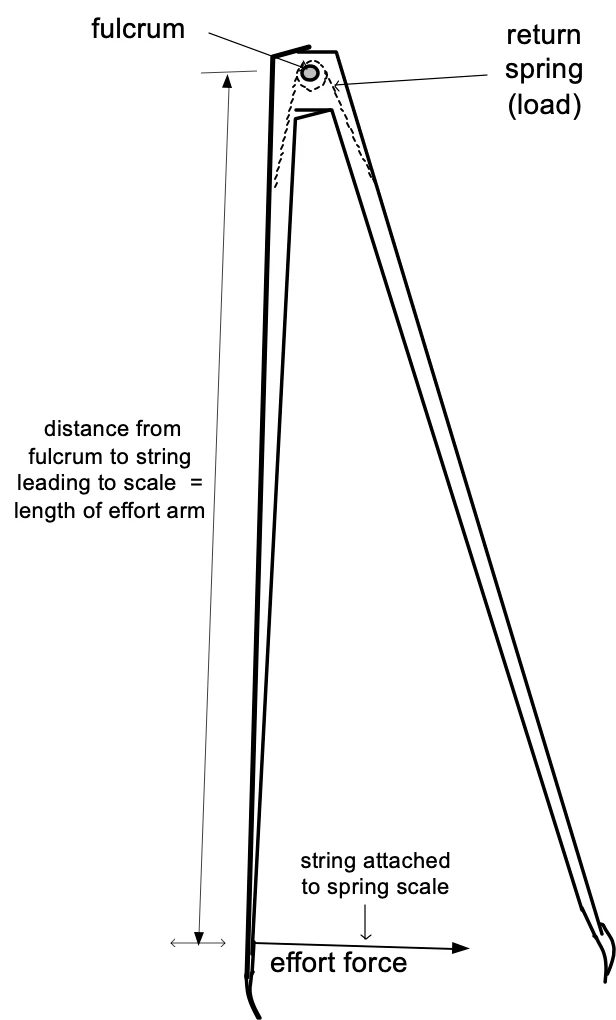

Figure 11 shows how to make the measurements. To measure distance conveniently, tape a ruler securely along one arm of the tongs, being careful to place the zero end of the ruler near the fulcrum. Pass a piece of string through the hole that holds the hook. Then use the string to fasten the spring scale around the arm at some point, measure the force on the spring scale, and record the distance of the string from the fulcrum using the ruler. If the string tends to slip, hold it in place temporarily with a little bit of tape. Be sure to hold the scale at right angles to the arm, and pull just enough so the arm is in mid-range between its open and closed positions .

Figure 11: Measuring both force and distance, using a spring scale and a taped-on ruler

Now ask students to make force and distance measurements at different locations along the arm. For each location, they should record both force and distance, and then make a table showing all of these measurements. Figure 12 shows some typical data.

| Distance (d) (inches) | Force (F) (Newtons) |

| 2 | 6.2 |

| 4 | 3.2 |

| 6 | 2.3 |

| 8 | 1.9 |

| 10 | 1.5 |

| 12 | 1.2 |

Figure 12: Typical force vs. distance data for a pair of salad tongs

What do you notice about this data? The force seems to go down as the distance goes up! Is there a way to operate on this data, so that a number comes out remains constant? Someone may come up with the idea of multiplying force times distance. Trying that out with the data shown in Figure 12 gives the results shown in Figure 1

| Distance (d) (inches) | Force (F) (Newtons) | Force times distance (Newtons) |

| 2 | 6.2 | 12.4 |

| 4 | 3.2 | 12.8 |

| 6 | 2.3 | 13.8 |

| 8 | 1.9 | 15.2 |

| 10 | 1.5 | 15 |

| 12 | 1.2 | 14.4 |

Figure 13: Data from Figure 12 with (Force x distance) column added

Notice that when force and distance are multiplied, the result comes out nearly the same each time! This happens because (force) x (distance) = a quantity called energy. Because energy can’t be created nor destroyed, the energy input to the device is always the same as the energy output, and the energy output is based on the return spring, which doesn’t change. In other words, the nearly constant values in the third column are an example of the Law of Conservation of Energy. Some students may ask why the results in the third column aren’t exactly constant. This is an interesting question, which can lead to a discussion of the many sources of error in this experiment.

Figure 14 shows that the distance we have measured should really be called effort arm, and the force is effort force. The load in this case is supplied by the return spring.

Figure 14: Force and distance measurements using lever terminology

Since the distance we have measured is really effort arm, and the force is effort force, the relationship we have discovered is:

(EFFORT FORCE) x (EFFORT ARM) = ENERGY INPUT= CONSTAN

If we measured the load arm and load force, we would find the same relationship, because the energy input at the effort must be the same as the energy output at the load, neglecting minor losses due to friction. In other words,

(EFFORT FORCE) x (EFFORT ARM) = ENERGY INPUT (LOAD FORCE) x (LOAD ARM) = ENERGY OUTPUT ENERGY INPUT = ENERGY OUTPUT

Therefore,

(EFFORT FORCE) x (EFFORT ARM) = (LOAD FORCE) x (LOAD ARM)

This important relationship, which was discovered by Archimedes, is called the Law of the Lever. By rearranging this equation with a little algebra, we reach the conclusion that:

This ratio, calculated either way, is what we have called MECHANICAL ADVANTAGE, commonly abbreviated M.A. Now we can see why. The purpose of many levers is to amplify the load force, for a given amount of effort force. Their ratio is the “bang for the buck” that expresses the “advantage” the lever provides. The equation show that this ratio can be calculated easily, just by measuring the lengths of the two arms, and taking their ratios. Because force goes up as distance goes down – a consequence of energy conservation – the ratios are inverted, depending on whether you are talking about force or distance. In other words, to maximize the load force for a given effort force, increase the effort arm relative to the load arm.

Another way to express mechanical advantage is provided by the relationship of ranges and arms that we discovered previously. From this, we can see three alternative ways of calculating mechanical advantage (M. A.):

This shows that the ranges of motion of the input and output ranges can be measured instead of the arms, and their ratio will also equal mechanical advantage.

Design Challenge

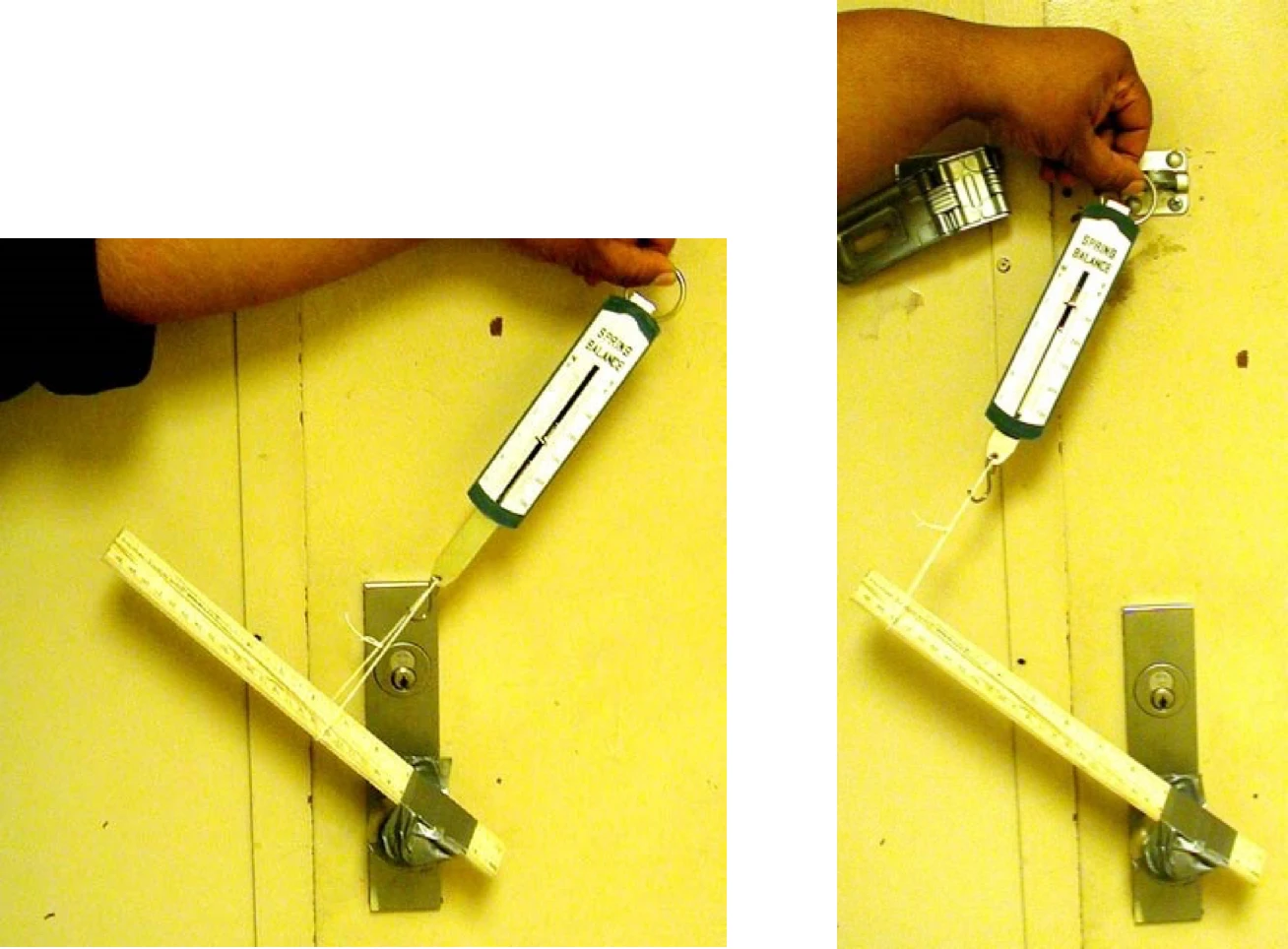

Procedure: Each group is asked to make a rotary device easier to turn. They can redesign the device by attaching a ruler with duct tape. Examples of rotary devices include a doorknob, door lock, faucet, cabinet handle, pencil sharpener, egg beater, hand drill, cheese grater (with crank input), or window opener. Then they test the solution by measuring force at various points along the arm.

The basic idea here is that the force goes down as the effort arm increases. By taping a ruler to a knob or handle, it is possible to extend the effort arm. To see how well it works, you can make force measurements at various points along the ruler. Figure 10 shows how a ruler can be added to make a doorknob easier to turn. Note that the force decreases as you move the scale towards the end of the ruler, increasing the effort arm.

Figure 15: Improving a doorknob by adding a ruler

This may not work. Figure 16 shows one thing that can go wrong: here the ruler is taped on the top of the doorknob, rather than the side. Notice how most of the effort goes into bending the ruler, instead of turning the doorknob! This can lead to a fascinating investigation of structures.

Figure 16: Ruler taped to the side of the doorknob instead of to the top